Greek-Australian specialist engineer creates his own Antikythera Mechanism

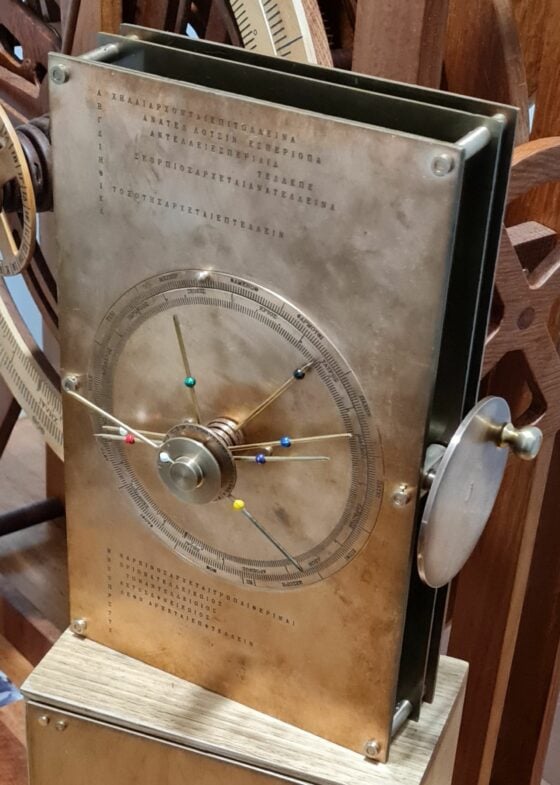

Nick Andronis with his bronze and wood interpretations of the Antikythera Mechanism. He has made available the plans for making them on his website. Photo: Supplied

While a team from the University of London made a big splash early in 2021 when it unveiled its 3D rendering of the famed Antikythera Mechanism, a Greek Australian living in Perth had already set about making his own computer rendering of the famous device and then built a larger wooden version followed by a bronze one that matched the original specifications. And he has made the detailed diagrams of his work available online for anyone to build.

Speaking to Neos Kosmos, Dr Nick Andronis PhD CPEng, a “semi-retired” chartered electronics, software, electrical and mechanical engineer said the famed mechanism whose function has exercised the finest minds since its recovery by Greek sponge divers off the waters of Antikythera island in 1901, was “a 2,200-year-old ancient Greek portable planetarium and the first known analogue computer marking the start of modern computing.”

Subsequent wars, invasions, sackings and lootings meant that there was no continuity between the achievement represented by the Antikythera Mechanism and the technological revolution of the past 300 years that have culminated in the “computer age”.

There is a gap of 1,000 years of Ancient Greek development that largely survived in the fragments of the writings of Arab scholars. We do not know the full extent Ancient Greek technology and the Antikythera Mechanism offers a tantalising glimpse of what may have been.

Dr Andronis said the Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero made reference to Greek mathematician Archimedes having a device that followed the courses of the five then-known planets of the solar system. While that reference is not conclusive it does suggest that there was more than one Antikythera Mechanism in existence at the time.

“Scholars have dedicated their lives to working out the 57 gears in the mechanism and how they work. A lot of technological skill went into its making,” said Dr Andronis.

Dr Andronis began work on his version of the Antikythera Mechanism five years ago. For him it was the process of making it rather than its use that drew him to the project which has cost him a pretty penny. “I lost count at $10,000. For me the mystery is the manufacture of the original mechanism which had parts numbers to suggest that more were made.”

He said the fact that it was made in bronze was probably one of the reasons why no other mechanisms have not surfaced today. Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, was often melted down and re-used for other purposes. The Ancient Greeks were masters in the use of bronze Most of the statues that they made, said Dr Andronis, were from bronze and not marble but few survive today because they were recast over the centuries for other uses.

“The Antikythera Mechanism is the culmination of 500 years of (astronomical and mathematical) knowledge and craftsmanship.”

It is the culmination not only of high technical skills but also of planetary observations and mathematical calculations and methods that have enriched our lives to this day.

“It is only after you build one and try to operate it for real that you understand the complexity and genius of the Ancient Greek design But it is impractical as a scientific instrument.” said Dr Andronis . It would have been easier for scientists of the day to rely on charts on papyrus that were easier to access and less likely to break down.

He first built a larger version of the mechanism in wood to work out how to make it bronze without the gears jamming.

“Bronze is awful stuff to work with, it chips like marble, which is probably why the Greeks were so good at working with it. It is also a natural lubricant and is still used in bush bearings in modern machinery.”

Having worked with and designed far more complicated equipment, Dr Andronis became more interested in the manufacturing process that would have gone into the making of the mechanism rather than its uses.

He theorised that the mechanism, whose individual parts display numbers, was made to a set a plan or blueprint which, in turn, suggests that more were made. He says that it was likely it was a product made for wealthy clients who wanted to impress with their knowledge of Ancient Greek astronomy. The front and back plates of the mechanism itself are etched with instructions for its use.

“It could have been part of an entrepreneurial exercise: making money selling a fancy instrument to the wealthy. Had it been a true scientific instrument it would have been 10 times the size and the gears would have been less likely to seize and break.

“If you wanted to make an authentic (Antikythera) mechanism, you would have needed to hand tools and you would also need a metal-working lathe to make gears that could hold the part with a wobble of less than 0.1mm. I deliberately used a low-quality lathe in making mine to see if it could be achieved.”

The question then is what type of device could have been used by the ancients to achieve that sort of precision in making the necessary parts.

“It would have required multiple craftsmen: a scribe to write the instruction manual and a scribe to etch the instructions on the front and back plates. There would have been skilled craftsmen to work the different parts. Different types of bronze were used, a soft bronze for the dials that could be engraved and a harder bronze for the gears. This means that there was an industry to make it.

“I feel a great sense of loss looking at the machine as it is part of our cultural heritage that has vanished. We need to make our community aware of the role of Greek science in our lives. When we send our kids to high school, the maths and sciences that they are learning today are derived from the Greeks.

“They were fiercely independent critical thinkers and that was the key difference with other civilisations of the time,” said Dr Andronis.

Σχόλια Facebook